Efforts to closely monitor online services before the last general election enabled cyber chiefs to detect ‘something weird going on’ – but quickly determine that the source was not hostile actors

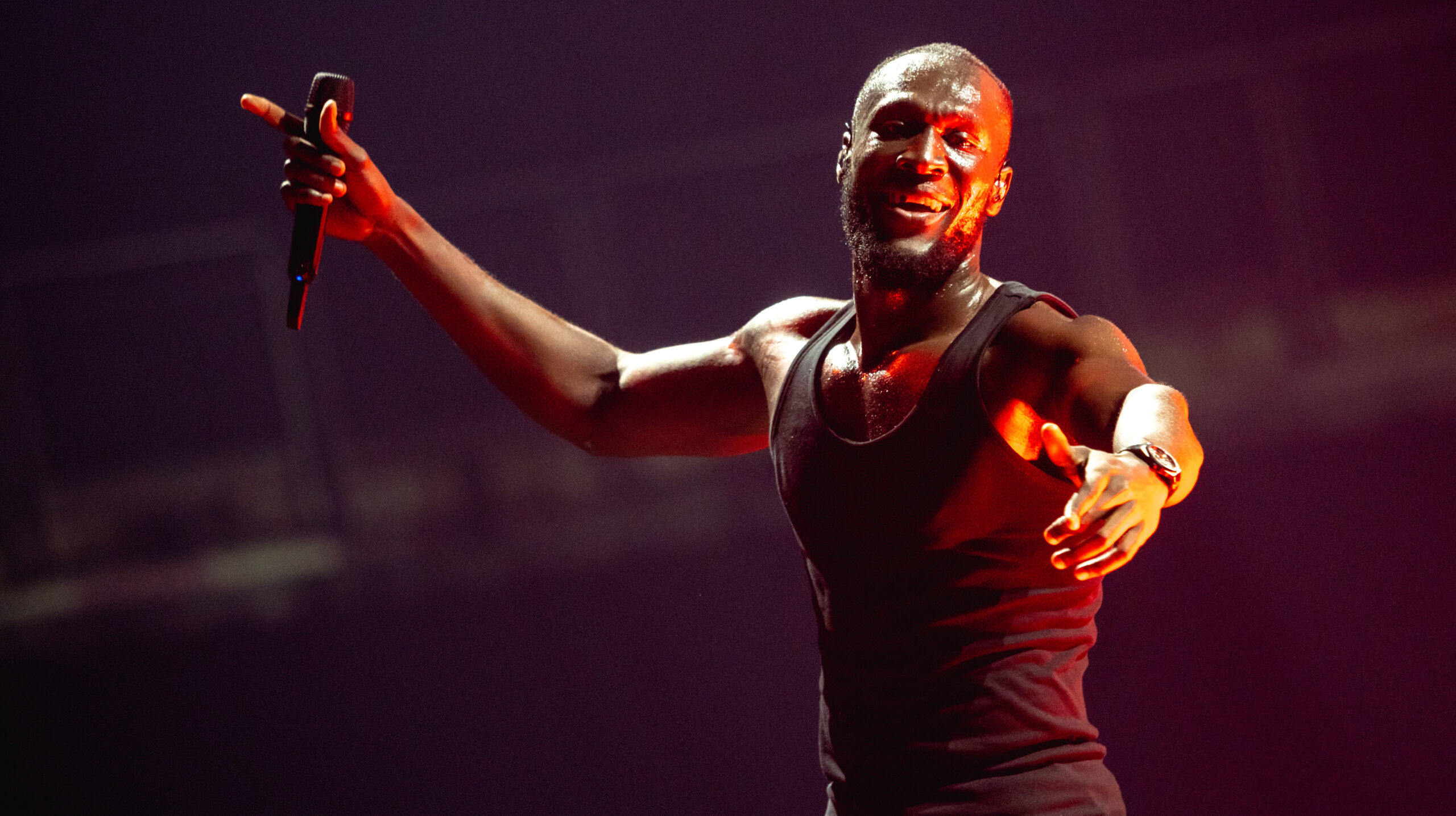

Credit: Ralph_PH/CC BY 2.0 DEED

An online post by the rapper Stormzy in the build up to the 2019 general election led to senior government figures holding an “emergency conference” to examine the possibility of “hostile foreign activity” intended to disrupt the UK’s democratic processes.

Three and a half years prior to the last election, government’s online Register to Vote service failed as the deadline neared for registrations to vote in the EU exit referendum.

According to Ciaran Martin, who was then the chief executive of the nascent UK National Cyber Security Centre, said that “the Government’s assessment [was] that was simply because of wrong profiling of the number of people who would be interested… [and] the system collapsed under weight of numbers [as] more people than expected registered to vote at the end” of the eligibility window.

As well as leading to a two-day extension to the registration deadline for the Brexit vote, the incident also meant that, in the run-up to the 2019 poll, cyber chiefs “stepped up a whole bunch of efforts” intended to ensure the stability of the online tools that support democratic processes.

Martin and his colleagues thus “watched ‘Register to vote’ very closely as the deadline approached” by which citizens were required to register. A little over 24 hours before the cut-off point set for midnight on Tuesday 26 November, officials once again saw a massive sudden increase in activity.

Related content

- How has the online voter registration service coped with 100,000 users a day?

- Cabinet Office floats multimillion-pound contracts to develop online voter ID service

- Bursting the bubble – the ethics of political campaigning in an algorithmic age

Martin, who was speaking during a recent evidence session of parliament’s Science, Innovation Technology Committee, said: “On the Monday evening at about 8.30pm we got an alert because the profile we expected was about 3,000 people using ‘Register to vote’ [at that point[ before the deadline. Suddenly, it spiked to 48,000. That was a big deal, but we spotted it immediately, in a way that we were not able to back in 2016.”

Having spotted what looked like an anomaly, senior officials held urgent discussions, and were ready to close down the online registration tool if a potential coordinated cyberthreat was detected. But it soon emerged that the cause of the increase was something much more innocent, and closer to home.

“That stood up an emergency conference and so forth and, ultimately, had it been hostile foreign activity the option could have been briefly to suspend the service,” Martin told MPs. “It turned out, on closer examination, that Stormzy had sent out a tweet encouraging people to register to vote, which led temporarily to a sixteenfold spike in use of the website.”

The former NCSC chief was answering a question from committee member Rebecca Long-Bailey about “the common challenges in detecting and mitigating cyberthreats across critical national infrastructure sectors”.

Martin said that the monitoring process of the online registration platform in the run-up to the last general election represented – and the response to the Stormzy-inspired spike – is “a really good story… from a cybersecurity point of view”.

“It shows that something weird is going on but you spot it immediately,” he said. “You don’t automatically say: ‘Let’s take it down’. You do the analysis and get the explanation. All the time there is what we call large-scale credential stuffing, where by brute force… that is guessing passwords and so forth—people say: ‘Right; I have a bunch of emails and a bunch of password – I will try this network and see how many I get’. It is being able to notice that anomalous behaviour and say: ‘Something weird is going on’. That is how that works in practice.”

Yasmine Lopez OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Only Fans Leaks Updates

Crii Baby RiRi OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Taylor Hall OnlyFans Mega Link Download

Taylor Hall OnlyFans Mega Link Download

Mulan Hernandez OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

North Natt OnlyFans Mega Link Download

Ima Cri Baby OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

TheRealRebeccaJ OnlyFans Mega Link Download

Daalischus Rose OnlyFans Mega Link Download

Updated Only Fans Leaks ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Caaart OnlyFans Mega Link Download

Mulan Hernandez OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Taylor Hall OnlyFans Mega Link Download

Hola Bulma OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

North Natt OnlyFans Mega Link Download

Hot 4 Lexi OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Buy Fansly Leaks ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Only Fans Leaks Updates

Emmanuel Lustin OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Only Fans Leaks Free Download

Mega Link Store

Hot 4 Lexi OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

North Natt OnlyFans Mega Link Download

Genesis Mia Lopez OnlyFans Mega Link Download

8TB Only Fans Mega ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Buy Only Fans Leaks ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Mega Link Shop ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Rebecca J OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Buy Mega Links ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Im xXx Dark OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

8TB Only Fans Mega ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Free Only Fans Leaks ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Im xXx Dark OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Buy Fansly Leaks ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Hola Bulma OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Gina WAP OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Taylor Hall OnlyFans Mega Link Download

3TB Only Fans Mega

Hot 4 Lexi OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Taylor Hall OnlyFans Mega Link Download

Ima Cri Baby OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Crii Baby RiRi OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Caaart OnlyFans Mega Link Download

Jenise Hart OnlyFans Mega Link Download

Lexi 2 Legit OnlyFans Mega Link Download

Rebecca J OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Only Fans Leaks Free Download

TheRealRebeccaJ OnlyFans Mega Link Download

GG With The WAP OnlyFans Mega Link Download

10TB Only Fans Mega ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Mega Link Store

Hola Bulma OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Mega Link Shop ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Daalischus Rose OnlyFans Mega Link Download

Taylor Hall OnlyFans Mega Link Download

Lexi 2 Legit OnlyFans Mega Link Download

Caaart OnlyFans Mega Link Download

Updated Only Fans Leaks ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Mikaila Dancer OnlyFans Mega Link Download

Rubi Rose OnlyFans Mega Link Download

Genesis Mia Lopez OnlyFans Mega Link Download

Leah Mifsud OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Gina WAP OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Lexi 2 Legit OnlyFans Mega Link Download

Gina WAP OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Buy Only Fans Leaks ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Itz Grippy TV OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Updated Only Fans Leaks ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Bulma XO OnlyFans Mega Link Download

Lexi 2 Legit OnlyFans Mega Link Download

Hot 4 Lexi OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Daalischus Rose OnlyFans Mega Link Download

GG With The WAP OnlyFans Mega Link Download

TheRealRebeccaJ OnlyFans Mega Link Download

Corinna Kopf OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Hot 4 Lexi OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Ima Cri Baby OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Yasmine Lopez OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Genesis Mia Lopez OnlyFans Mega Link Download

Updated Only Fans Leaks ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Yasmine Lopez OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Barely Legal Lexi OnlyFans Mega Link Download

Yasmine Lopez OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Corinna Kopf OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Mega Link Store

8TB Only Fans Mega ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Its Lunar Liv OnlyFans Mega Link Download

Buy Mega Links ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Ima Cri Baby OnlyFans Mega Link Download ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

Buy Leaked Content ( Visit https://archiver.fans )

GGWithTheWAP Mega Folder Download ( https://urbancrocspot.org/gina-wap-gg-with-the-wap-only-fans-mega-link-9gb/ )

Sammy02kVIP OnlyFans Leaks Mega Folder Link Download ( https://CrocSpot.Fun )

GinaWAP Only Fans PPVS Download https://urbancrocspot.org/tag/gg-with-the-wap/

The Real Bombshell Mint ( https://urbancrocspot.org/the-real-bombshell-mint-only-fans-mega-link/ )

KorinaKova OnlyFans Leaks Mega Folder Link Download

Tytiania Sargent Porn ( https://UrbanCrocSpot.org/shop )

EmpressElfiie LittleElfiie OnlyFans Leaks Mega Folder Link Download

GGWithDaWAP Only Fans Leaks https://urbancrocspot.org/tag/gg-with-the-wap/

Cubana Redd OnlyFans Leaks Mega Folder Link Download ( https://UrbanCrocSpot.org )

The Real Bombshell Mint Only Fans Leaks ( https://UrbanCrocSpot.org/ )

BabyGirl213 OnlyFans Leaks Mega Folder Link Download ( https://CrocSpot.Fun )

GGWithTheWAP Leaks ( https://urbancrocspot.org/gina-wap-gg-with-the-wap-only-fans-mega-link-9gb/ )

Bombshell Mint OnlyFans Leaks ( https://urbancrocspot.org/the-real-bombshell-mint-only-fans-mega-link/ )

Pornstar

Porn site

Sex

Viagra

https://doxbin.org/upload/JayceBradfordChildPredatorCPConnoisseur